No orchestra season would be complete without revisiting some of the great chestnuts of the repertoire. This week the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra (CPO) will be playing just such a concert, and while the repertoire is familiar it’s an opportunity to be reminded that the greatest works improve with repeated listening since their depths become more apparent as the listener’s understanding grows. This is one of the most rewarding things for us musicians, who play works old and new, familiar and exotic, year after year.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s Capriccio Espagnol is a delightfully colourful, virtuosic work. Other than the second movement variations on a wistful lyrical theme, the other four are all Spanish dances, and they take advantage of the sonic capabilities of the orchestra. Most notable is the beginning of the fourth movement: a series of solos for various instruments ranging from declamatory to beguiling.

Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini is more compact and somewhat less serious in tone than his three concertos, and it shows off the composer’s reimagining of a theme from a violin caprice in characters atmospheric, bombastic, puckish, and passionate. The very famous Variation 18 is based on an inversion of the main theme, which is to say that the melody is turned upside-down. This type of manipulation of a theme goes back hundreds of years, to the age of Bach and before. Rachmaninoff uses much of his own musical language in these variations; these cannot be mistaken for the work of another composer. But he also draws on some of the outside sources he reaches for in his other works, for example the distinctive Dies Irae motif from an often-quoted 13th century Gregorian chant plays a central role in this piece and many of the composer’s others.

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 is as much of a chestnut of the repertoire as a piece can be. Almost any person you could ask would have to admit at least recognition of the opening bars. But in addition to the first movement, the rest of the piece is also quite remarkable. You’ll hear that so-called “fate” motif, those short-short-short-long notes, used all throughout the symphony, in obvious and less obvious ways, giving all four movements a strong sense of unity.

Beethoven also draws on the past as well as his own inspiration: a variation in the second movement takes the harmony of the tune “La Folia”, a popular choice for writing variations for hundreds of years before Beethoven; and the opening notes of the third movement are the same as the last movement of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40. The fifth is also a very innovative symphony, having made the trombones and piccolo part of a serious symphony for one of the first times, and establishing them as part of the family.

It’s easy to take the hits for granted. These works by Rimsky-Korsakov, Rachmaninoff, and Beethoven are the bread and butter of an orchestra, but it’s always worth taking care to really listen and understand anew just how wonderful these old friends are.

|

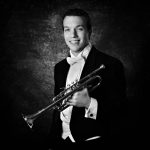

Written by Adam Zinatelli, Principal Trumpet |